Crisis On the Waterfront

This week, how coastal cities are at risk of flooding, and why Indian trains continue to be delayed

Dear Reader

The 30th global climate conference or Conference of Parties (COP30) is under way. For India and many other countries in the Global South, the annual affair is an opportunity to hold developed countries accountable for their historical emissions. Climate finance is critical to help developing nations move away from fossil fuels and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

What countries finally agree on this year could become clear by the time we write to you next, but this week, my colleague Tanvi Deshpande wrote about the impacts that communities could see in India’s coastal cities.

Elsewhere, the country’s railways continue to be strained, leading to a drop in the punctuality index—which in itself is quite lenient compared to global benchmarks.

By the Bay

Waterfront property sells for a premium in most Indian cities—and ‘sea-facing’ apartments some kilometres ashore also charge huge rents. But as India’s coastal cities build closer and closer to the sea, they are at increasing risk of flooding and inundation driven by a warming world and the now-frequent extreme weather events.

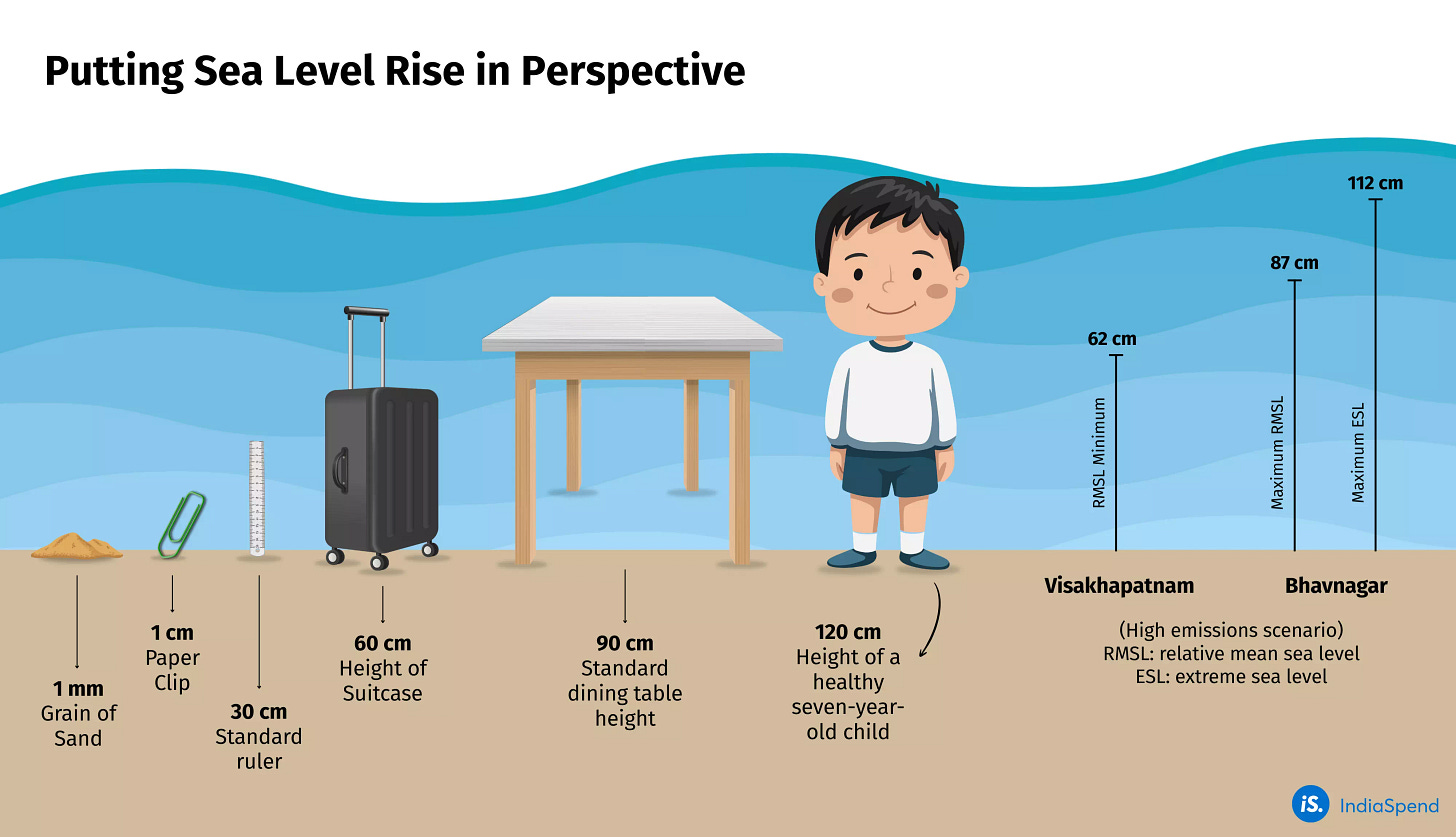

Future projections of relative mean sea level indicate a rise all along the Indian coasts ranging from 62 cm in Visakhapatnam to 87 cm in Gujarat’s Bhavnagar under a high emissions scenario.

More frequent storm surges and tidal waves can cause further damage to cities such as Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. Bhavnagar, for instance, could see levels rise up to 112 cm, researchers estimate.

For context, 60 cm is about the height of a suitcase, 90 cm is roughly a standard dining table, and 120 cm is the height of a healthy seven-year-old child.

It is crucial to embed climate-resilient infrastructure into cities’ long-term urban planning systems as a defence against sea level rise, Tanvi Deshpande reports.

Running Late

Indian trains are considered to be punctual if they arrive within 15 minutes of scheduled time. This is much more lenient compared to Germany’s 5 minutes, Britain’s 10 minutes, or Japan’s few seconds. But even by that standard, India’s punctuality index fell post-pandemic.

The issues are mostly long-standing. For instance, 55% of India’s tracks are single-lined, and the pace of doubling is slower than needed to improve average speeds. Secondly, tracks are capable of handling speeds ranging from 110-130 kmph, but permanent speed restrictions on some stretches create bottlenecks.

Over 80% of India’s busiest rail routes—the High-Density Network connecting major cities—are running over capacity. At least 22% are so congested that their capacity utilisation exceeds 150%. This leaves little time for maintenance and overhaul, and can lead to delays or worse—accidents. And signal faults also contribute to delays and accidents.

India has achieved near-universal electrification of tracks, but some lines do not have end-to-end coverage, the country still has more than 4,400 diesel locomotives prone to failure, and when they fail, they block entire stretches of tracks until relief engines can move them.

Put together, this complex web of issues needs a strategic shift in planning and overhaul, but until that happens, trains continue to run late, Prachi Salve reports.

Have a good weekend!