The Age of Cyber Crime

This week, data deep dives into India’s rising cyber crime incidence, and how geography dictates food prices

Dear Reader

Do you remember what you were doing when the Prime Minister announced the scrapping of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes back in November 2016? I was at the IndiaSpend office in Mumbai, editing copy and watching a colleague on TV explain the findings from our #Breathe network of low-cost air quality monitors.

That night, I borrowed Rs 200 from a friend and got home. The next morning, I started using digital payments. It wasn’t just me, of course. The country saw wide adoption of digital payments over the next few weeks.

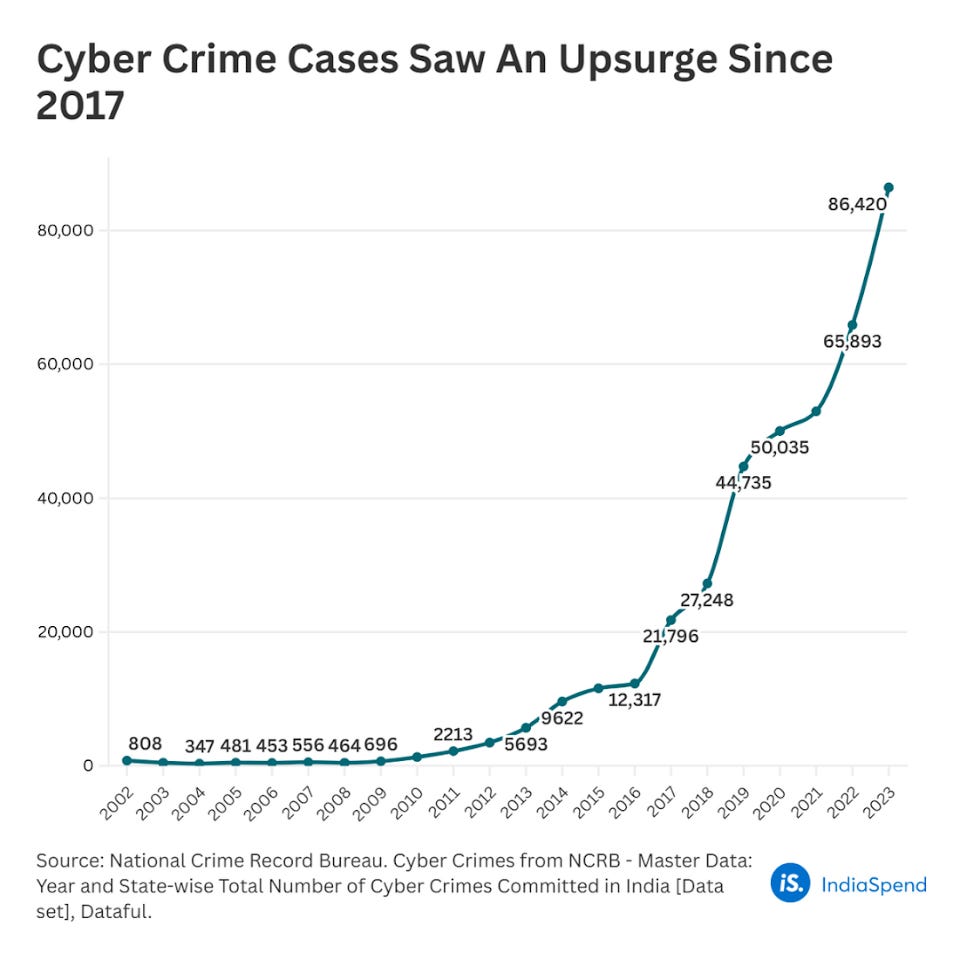

So when my colleague Vijay Jadhav pointed out that India saw a 77% increase in cyber crime reporting in 2017, it all fell in place. These were the years that India saw rising mobile phone and internet access, without a corresponding increase in digital literacy and safeguards—leading to an increase in incidents. This was also when the JAM trinity—or Jan Dhan accounts, Aadhaar and mobile—was being aggressively implemented.

A caveat: Crime data are rarely straightforward. An increase in registration does not necessarily mean more crime. It could be the result of higher reporting and easier registration. But corresponding data from the Reserve Bank of India on volumes of financial fraud also concur. We explain the trends in four charts.

Elsewhere, we bring you more insights from our realtime dashboard, Food Price Watch.

Fraud, Digital Arrests & Other Crises

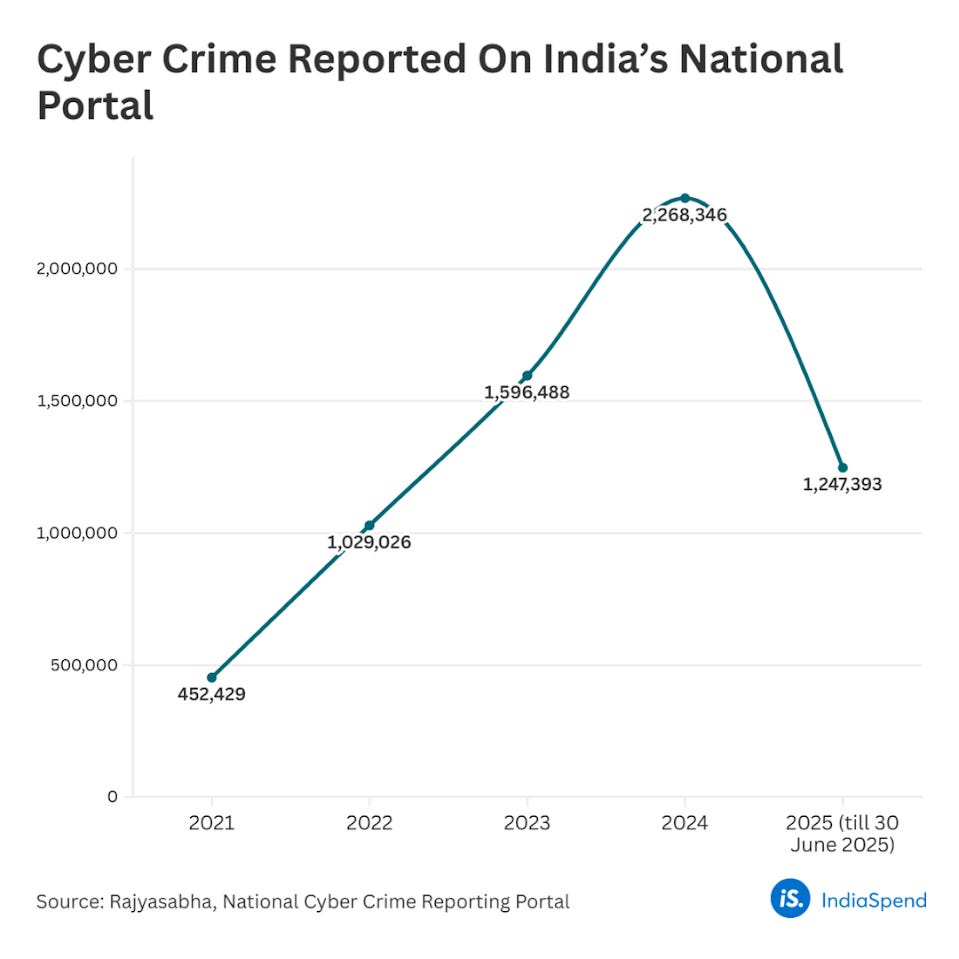

There are two major sources of data for cyber crime. First, citizens can report cases on the National Cyber Crime Reporting Portal. The portal categorises cyber crime into three broad categories: Women/children-related crime, financial fraud, and other cyber crime. Complaints rose from 452,000 in 2021 to 2.3 million in 2024, a five-fold increase.

Second is the National Crime Records Bureau’s annual report, which collates case data from across the country. Cases of cyber crime more than tripled between 2018 and 2023. The sharpest increases, as I said, came after 2016.

RBI data show that digital payment frauds in cases involving losses above Rs 1 lakh are now 11 times higher, and the total money lost is 12 times more than in 2020-21.

Finally, cases of digital arrest scams jumped from 39,925 in 2022 to 123,672 in 2024, while reported losses rose from Rs 91 crore to Rs 1,935 crore.

Research suggests there are several reasons for the increase—from lack of awareness and increasing sophistication of frauds, to untrained police personnel and evolving state of laws. Vijay Jadhav analyses the data.

In the Distance, Dearth

Food prices in India have been subdued this year. However, not all citizens have had a chance to experience this reprieve: in Kerala, Lakshadweep and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, food prices rose by more than 4% compared to last year, as per the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

This is also borne by data from the Ministry of Consumer Affairs. The cost of essential food items fell everywhere in the country, but some foods were more expensive in the North East and Ladakh in October this year. Rains disrupted supply chains in Himachal Pradesh, whereas bandhs and strikes are a frequent phenomenon in the north east—highlighted in a parliamentary standing committee report as well.

In November 2025, Mizoram recorded the country’s highest daily grocery cost (Rs 77.5) for the simplest diet that meets nutrition requirements, far above the all-India average and driven by logistical constraints typical of Himalayan and northeastern states. Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Ladakh also faced elevated prices for essential pulses, vegetables and oils, Food Price Watch shows.

The climate of the Himalayan region is favourable for growing fruits and vegetables. If put to sustainable use, these areas can play a crucial role in ensuring food and nutrition security in India, Nushaiba Iqbal writes.

Have a good weekend.