The Business Of Healing

Also this week, how Haryana's farmers are dealing with crop damage due to nilgais, and the untapped potential in using treated wastewater

Dear reader

Twenty six tourists were shot dead and many others injured by terrorists in Kashmir’s Pahalgam, the deadliest attack on civilians in years. India has announced a slew of measures in response, including holding the Indus Water Treaty in abeyance, and setting deadlines for Pakistanis to return home.

A father of two children from Pakistan’s Sindh appealed to both governments to allow them to stay in India for treatment—the children are being treated for a heart condition in New Delhi. But medical visas are set to be revoked as of April 29, which brings me to our first story of the week.

In six years to 2024, over 1,200 Pakistani patients were issued medical visas, including 225 just last year. India ranks 10th on the 2020 Medical Tourism Index, attracting nearly half a million patients annually from across the world. And diplomatic ties play a significant role in who can avail treatment here.

Since the 2021 regime change in Afghanistan, visas for medical tourism issued to Afghan nationals fell from over 20,000 to just one last year. Hospitals also expect a drop in visas issued to patients from Bangladesh, following the political upheaval in that country.

Nushaiba Iqbal spoke with patients and their families from the Philippines, Turkmenistan and Iraq, hospitals and service providers around them—who are evolving to cater to foreign nationals. Read Nushaiba’s story to understand how India is turning into a popular medical tourism hub.

Habitat destruction and development are pushing the nilgai towards human settlements, leading to conflict and heavy losses for farmers in Haryana. Studies suggest that the blue bulls can damage as much as 27% of farms in western Haryana, sometimes resulting in losses worth over Rs 17,000 per hectare.

India is home to about 100,000 nilgais, estimates show. The antelope, which gets its name from its cow-like horns and tail, and blue-grey hued skin, is revered by the Bishnoi community, a Hindu Vaishnava sect.

To tackle the conflict, many farmers engage caretakers armed with muzzle-loading rifles to guard the farms. But these caretakers sometimes end up killing the animals, selling their meat for as little as Rs 80 per kg, including to high-end hotels which see demand for ‘exotic’ meat. The complex situation has led to the formation of local poaching networks that could seriously impact local ecological balance, Romita Saluja reports.

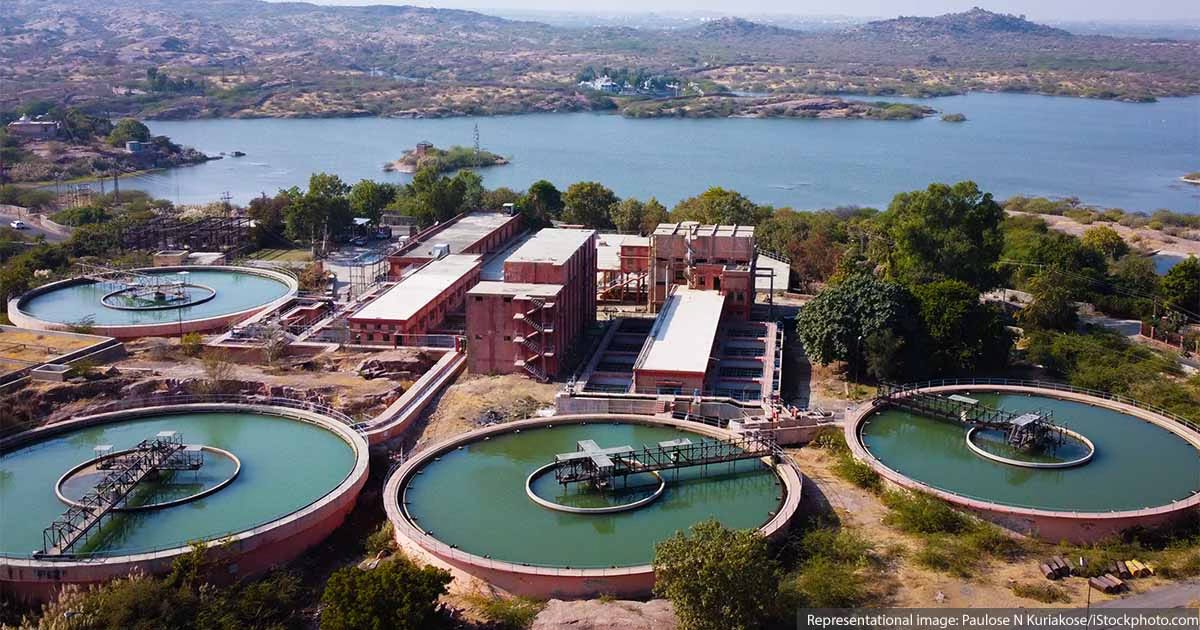

At COP29, the global climate conference in Azerbaijan last year, delegates were offered a Singaporean beer with a twist: The beer was made using treated sewage water. The move illustrated the increasing water stress in various parts of the world, and the potential that treating wastewater for reuse holds.

Back here in India, only two states hold the capacity to treat all the sewage they generate, but even then, the plants do not run at capacity. The result? Only about a quarter of the country’s sewage is treated, while the rest ends up in water bodies, polluting them.

As early as 2030, India’s water needs are expected to be double the amount of its supply. With rising population, increasing urbanisation, and rapid depletion of ground and surface water, India needs to urgently increase its treatment capacity, and channel treated water for non-potable uses such as cooling, road cleaning, irrigation of horticulture crops, and flushing, Jency Samuel writes.

For IndiaSpend Hindi, Parkishit Nirbhay explains how inadequate screening, undertrained healthcare workers, and insufficient public awareness threaten to derail India’s journey to being leprosy-free by 2027.