The Canary in the Coalmine

This week, the faltering revenues of India's panchayats, the shifting profile of India's 10 million teachers, the mandatory teacher eligibility test and more

This week, the spotlight is squarely on India’s education system. From the financial fragility of panchayats that fund schools, to the shifting profile of India’s 10 million teachers, to a Supreme Court ruling that has left lakhs of serving teachers anxious and, finally, to the stark contrast between Himachal Pradesh’s “fully literate” claim and the ground reality of teacherless classrooms.

Together, these stories trace how structural gaps, policy choices, and administrative neglect ripple down to the classrooms that shape the future of India’s children.

Panchayats stuck in dependency trap as revenues collapse

More than three decades after India gave constitutional status to rural local bodies, most panchayats remain financially weak and heavily dependent on state and Union government grants.

A new Ministry of Panchayati Raj expert committee report finds that between 2017-18 and 2021-22, panchayats’ own revenues fell by 10.5%, amounting to just ₹59 per capita. In some states, grants account for 95% of panchayat finances, leaving little room for independent planning or innovation.

Gram panchayats, meant to serve as grassroots institutions of self-government, face a mix of outdated tax rates, missing collection rules, limited control over common property resources and acute staff shortage. While southern states like Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh show stronger performance, most states’ finance commissions remain ineffective. Experts warn that this “dependency trap” undermines local accountability and self-reliance, eroding the spirit of the 73rd Amendment and weakening India’s vision of empowered rural governance. Priya Verma reports

India’s teachers: More women, higher degrees

India’s teaching workforce crossed 10 million in 2024-25, with government schools still employing the largest share, though private unaided schools are catching up fast.

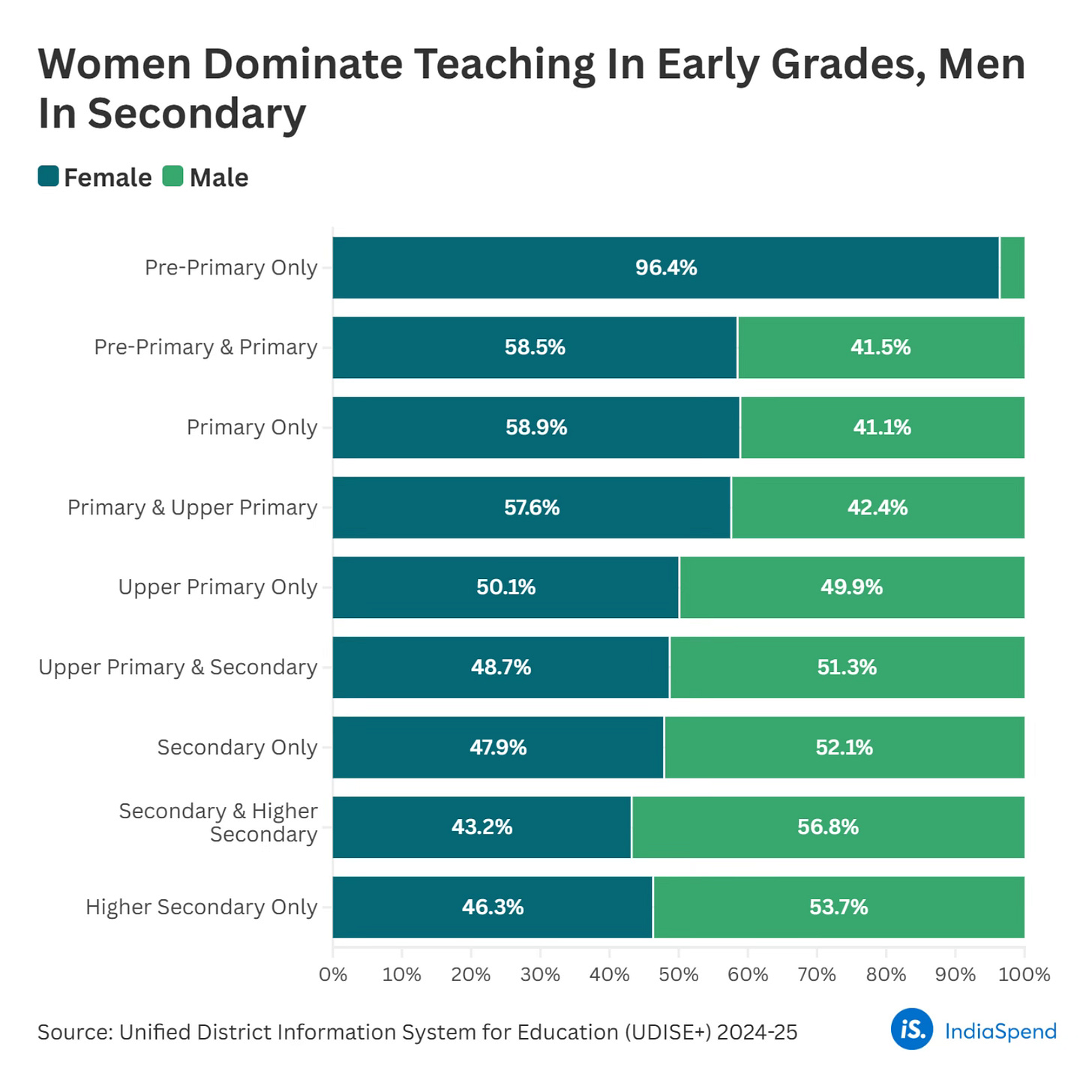

Women now make up 54% of all teachers, but men dominate at the secondary and higher secondary levels. The average number of teachers per school rose to seven, while single-teacher schools declined by 12%.

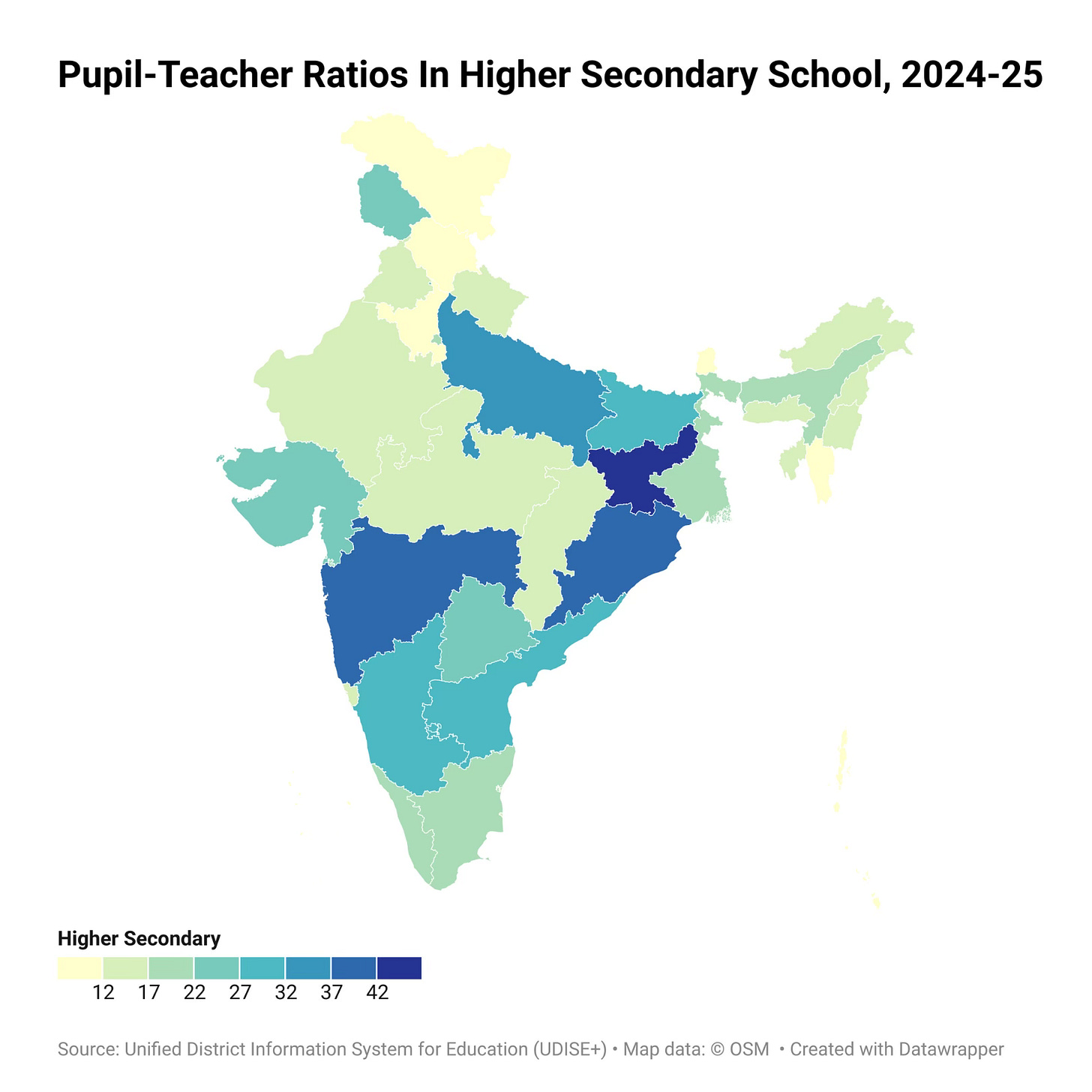

Pupil-teacher ratios improved nationally to 24:1, yet several large states, particularly Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Odisha, and Uttar Pradesh, still exceed the 30:1 benchmark at the higher secondary level.

Teacher qualifications are rising, with nearly nine in ten holding at least a bachelor’s degree, but professional training has declined, raising concerns about classroom readiness. Meanwhile, non-teaching staff has shrunk by 22%, leaving just one support worker for every 14 teachers.

In six charts, Vijay Jadhav maps these shifts, offering a closer look at how the country’s teaching corps is expanding, feminising, and becoming more qualified, and yet increasingly overstretched.

Supreme Court makes TET mandatory; 2-Year deadline spurs protests

A Supreme Court order on September 1 has made the Teacher Eligibility Test (TET) compulsory not only for new recruits but also for serving teachers nationwide.

The bench of Justices Dipankar Datta and Augustine George Masih ruled that teachers with more than five years of service remaining must clear TET within two years or face resignation/compulsory retirement while those with five years or less must pass TET to be eligible for promotion. The court clarified that even pre-2011 appointees fall under this requirement, while the question of minority institutions will go to a larger bench.

The decision has triggered protests across states, notably in Uttar Pradesh where unions argue the rule retroactively alters service conditions and excludes categories ineligible for TET under current. UDISE+ data underscore the challenge: over 900,000 teachers nationwide are below graduate level, including 50,000-plus in UP. Unions plan statewide actions and demand legislative or regulatory relief, phased timelines, or alternative compliance pathways. Mithilesh Dhar Dubey reports for IndiaSpend Hindi

‘Fully Literate’ on paper, teacherless on the ground

On September 8, Himachal Pradesh declared itself a “fully literate state,” boasting a 99.3% literacy rate and the best student-teacher ratio in India. Yet in Chamba district’s Ludera village, the government primary school has been without a permanent teacher since May 2025, when its last teacher retired. A peon was also transferred in August, leaving only the building and children behind.

Despite three separate transfer orders, no teacher has joined; some resisted postings, others had orders cancelled. The school now runs on ad-hoc deputations, disrupting learning for 28 students just months before their exams. Parents and the School Management Committee have filed complaints, while RTI responses confirm the vacancies.

Officials admit that around 30 schools in the district rely on deputation, without permanent teaching staff. The matter has reached the High Court, but the government has yet to file its reply. Critics say this neglect undermines children’s constitutional right to free and compulsory education under Article 21A. Surinder Kumar reports for IndiaSpend Hindi

These four stories underline an unnoticed problem. On the one hand, India celebrates its “demographic dividend” and projects its young population as a driver of future growth and, on the other hand, the four stories above underline the sobering truth that systemic neglect of the education sector risks shackling that very generation.

From panchayats stripped of fiscal autonomy, to teachers overburdened and under-supported, to court orders that threaten livelihoods instead of strengthening classrooms, to “fully literate” states where children sit in teacherless schools, the dissonance is glaring. Without urgent reforms and accountability, the promise of India’s youth risks becoming a hollow boast, with tomorrow’s workforce held back by today’s failures in ensuring the basics of education.

We'll see you next week, with more stories that matter. Be well.