When Trees Disappear and Cities Turn Into Ovens

This week, the Urban Heat Island effect that's bound to get worse, and an interview on research into what could turn out to be the next pandemic

Dear Reader

How do abstract crises—rising temperatures, emerging viruses, disappearing green cover—translate into everyday struggles?

This week, two stories answer that in starkly different ways.

The first, a two-part series, is about something you can feel: heat. In Chennai, a retired nurse watched her neighborhood’s shade trees disappear over 40 years. In Bengaluru, a delivery worker feels temperatures her phone doesn’t register. In Delhi, a tailor lost two-thirds of her income because indoor heat makes work unbearable.

The second is about something you can’t see yet: a potential pandemic. Researchers modeled what happens if bird flu spills over from poultry to humans in India. Their finding: Once the virus escapes farm workers’ families, only lockdowns can contain it.

Both stories reveal how invisible transformations—satellites document cities turning from green to grey; researchers simulate virus transmission through synthetic populations—manifest as lived realities for real people.

It’s Getting Hotter

D. Tamilselvi worked as a community health nurse in Chennai for 40 years. “In the beginning, I remember always having tree shade to park my cycle. Around the turn of the century, the trees disappeared. I began to sweat and struggle in the heat even in October.”

Her experience isn’t isolated. Indians were exposed to 19.8 heatwave days on average in 2024—a third of which wouldn’t have occurred without climate change. Heat exposure led to a loss of 247 billion labor hours, or $194 billion in income. By 2030, India will lose 5.8% of daily working hours to rising temperatures.

The governance failures are stark: master plans exist but experts say government departments don’t coordinate on heat stress. Heat Action Plans are underfunded and poorly targeted. On the ground, builders violate green cover rules through “connections and corruption.”

Cool roofs can lower temperatures 4-5°C. But experts warn retrofitting tier-1 cities may be nearly impossible. “Where is the space to improve green cover? There is rampant illegal construction. Tier 1 cities are almost beyond repair,” says climate resilience consultant Abhiyant Tiwari.

The hope lies with tier-2 cities. Tamil Nadu is studying heat block by block. Madurai is creating urban forests. Patna’s 2031 master plan focuses on urban greening. Priyanka Thirumurthy reports.

The Heat From Up High

In part two of the series, we analysed satellite data from nine cities spanning up to 50 years:

Bengaluru: Built-up area grew 1000% while vegetation shrank 88%. Land surface temperature rise: 15.13°C in 30 years—classified as “severe and hazardous”

Vijayawada: Temperatures rose from 25.51°C to 41.35°C (+15.74°C) in 22 years

Hyderabad: Green cover tripled yet temperatures rose. Why? “Forest cover lost to rapid urbanization can’t be replaced by scattered planting. They grow eucalyptus because it matures fast but evapotranspiration capability is low,” explains urban researcher D. Sabarinath

Mumbai: Water bodies declined 24%, creating 6-8°C temperature differences between neighborhoods just 2 km apart

Chennai: Water bodies encroached from the 1990s, now records Tamil Nadu’s highest nighttime temperatures

Tier-1 cities may have exceeded their thermal capacity to reverse heat intensification. Tier-2 cities still have a choice—but only if they act on what satellite data has made impossible to deny. Read Priyanka’s story here.

Preparing for the Next Pandemic

While cities grapple with heat today, researchers are modeling a crisis we can’t yet see: a potential bird flu pandemic.

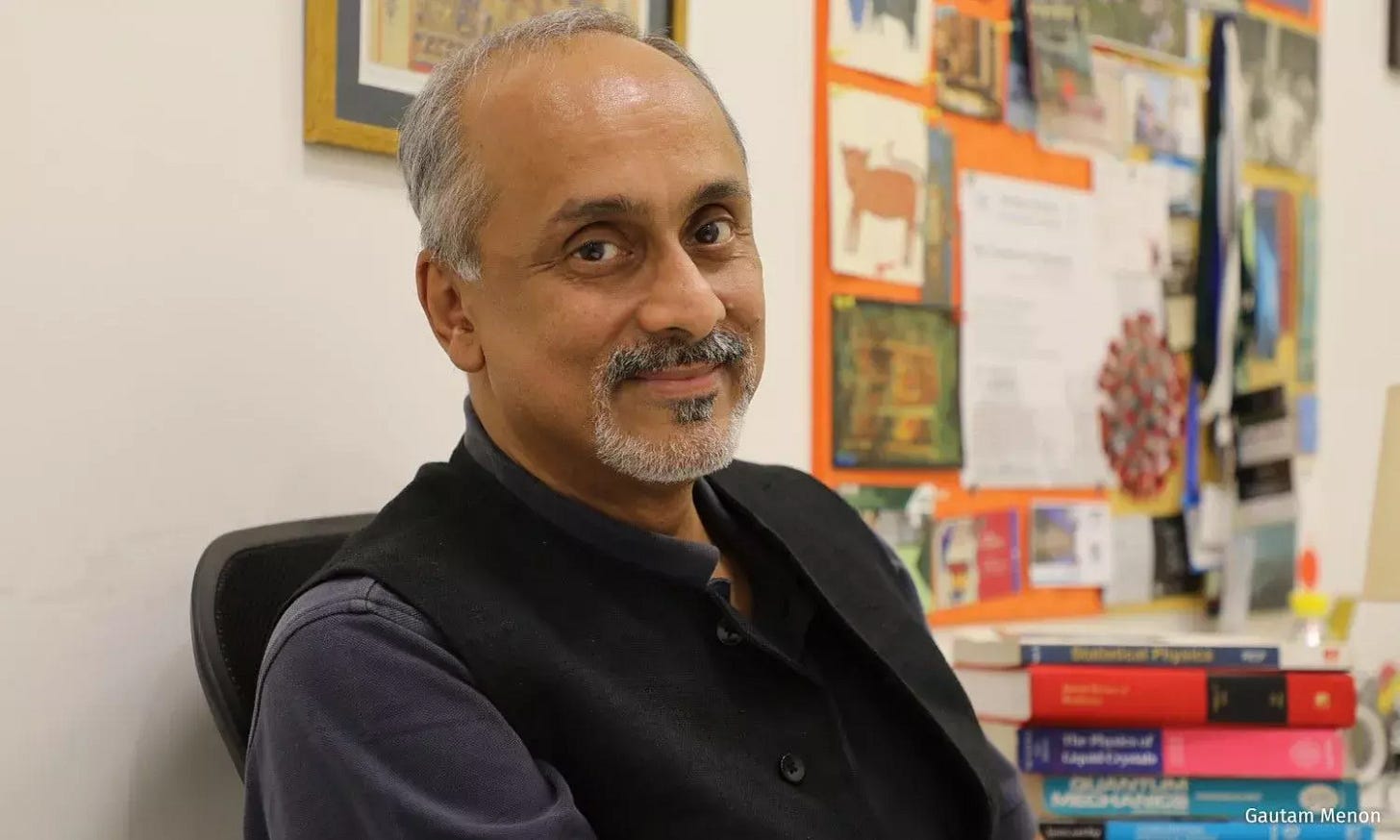

Gautam Menon, professor at Ashoka University, and his team used BharatSim—an ultra-large-scale simulation—to model H5N1 spillover in a Tamil Nadu poultry district. The finding: timing is everything.

“If we imposed quarantining when the number of cases was between 2 and 10, we could ensure the disease did not spread,” Menon told me in an interview. “But beyond 10 cases, it would have escaped the immediate circle of contacts, to expand far more unpredictably and uncontrollably. At this point, only large-scale interventions such as lockdowns can help.”

The virus can’t yet pass sustainably between humans. But if it acquired that ability, the spread could resemble COVID-19—with one crucial difference: a fatality rate of 30-40% versus COVID’s 1-2%.

“The costs in terms of mortality would be far larger,” Menon explains. “It would be more reminiscent of the 1919 Spanish Flu pandemic in India, which saw the largest number of deaths in the world.”

India has infrastructure from COVID—testing capacity, vaccine production, oxygen plants. But, much of it may have deteriorated.

“Government interventions should be light-touch and not heavy-handed,” Menon says. “Communication is paramount. Above all, public health messaging must remain transparent and accountable. People have a right to know.”

He emphasises avoiding COVID-era mistakes: performative measures like night curfews that made no public health sense, demonisation of communities (Tablighi Jamaat), lack of transparency that eroded trust.

“It is also easy to squander trust. If political messaging is the goal and not validating what people can see through their own eyes, trust will suffer.”

Read the full interview here.

The cost of delayed action rises sharply over time. Whether it’s preserving green cover before concrete sets or quarantining infections before they escape family circles, the easiest interventions work only if implemented early—before crises become visible to everyone.

Have a good weekend!