Whose Road Is It Anyway?

This week, the trends in road accident deaths, and the mental health impacts of extreme weather in the Sundarbans

Dear Reader

India’s road accident data have many flaws: As we had reported in October 2021, the government uses only police data to report road accident fatalities, ignoring sources such as hospitals, state and district level transport departments. For instance, if someone dies 30 days after an accident–as is possible in cases of grievous injury–it does not count as a road accident death.

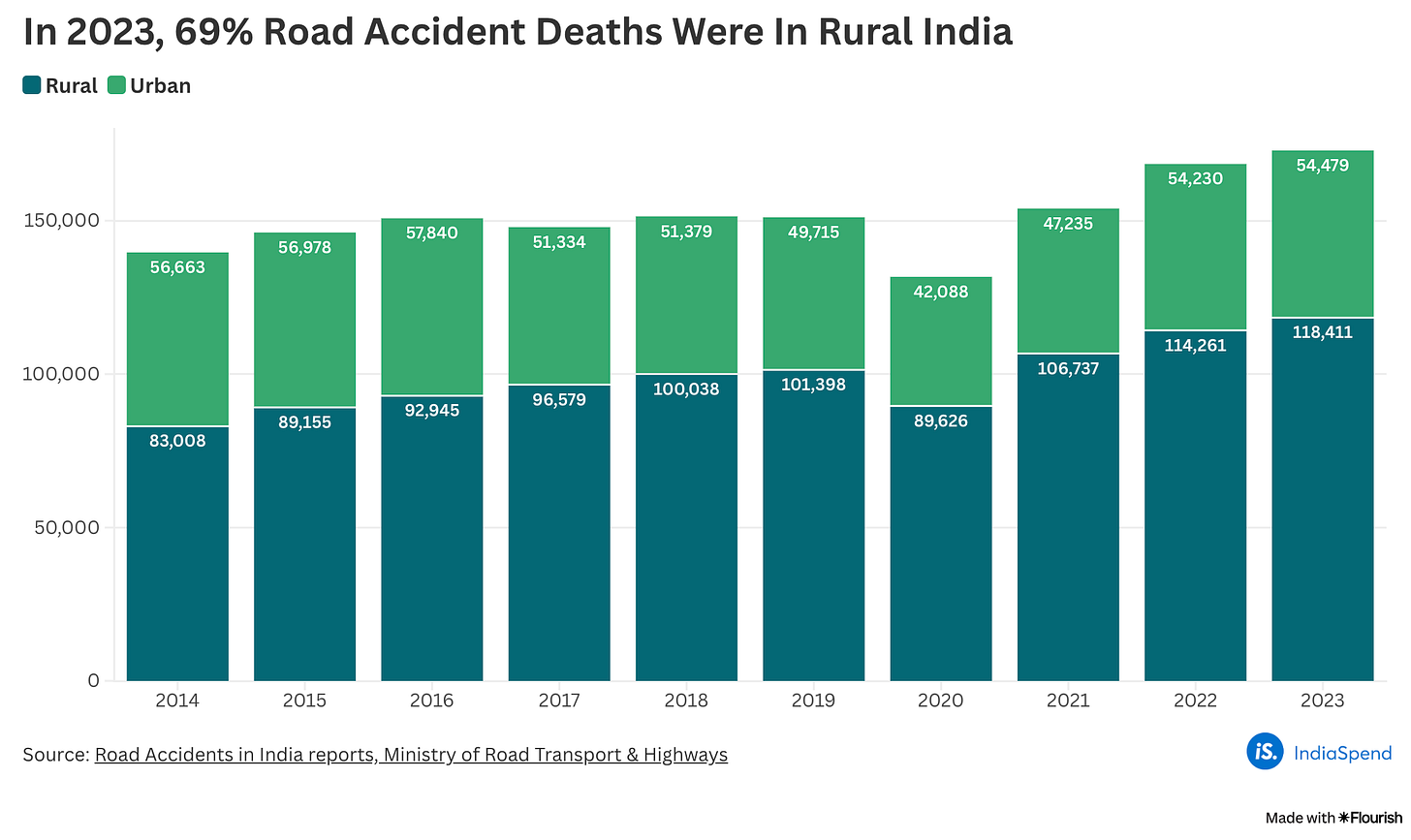

But even with the limitations, data for the year 2023 released recently show a worrying trend: Indian roads are increasingly becoming more dangerous for its most vulnerable users.

Elsewhere, repeated displacement and exposure to extreme weather on India’s vulnerable eastern coastline is leaving communities with lasting mental health issues, often ignored in official response.

The Crisis On Two Wheels

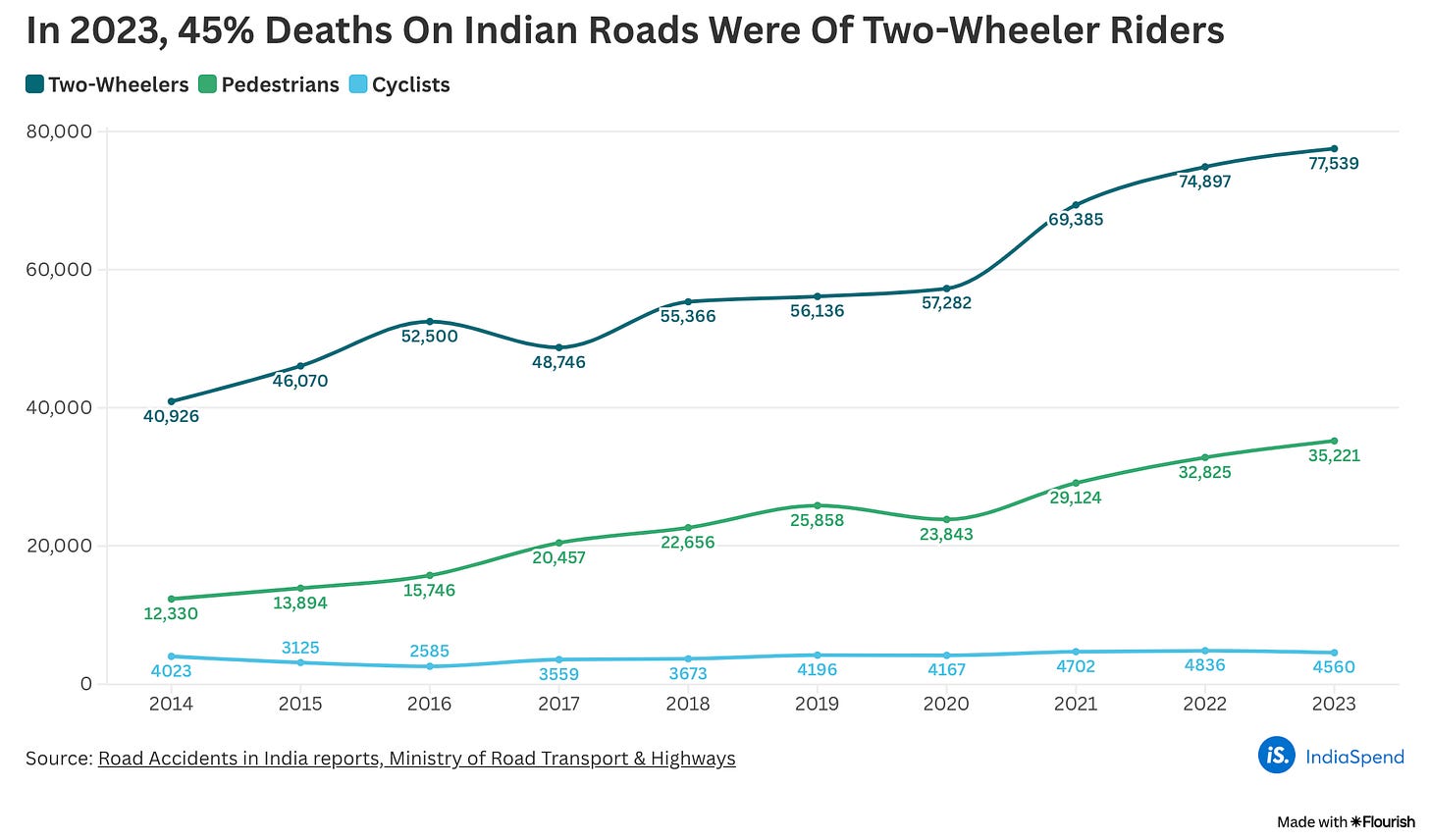

A decade ago in 2014, five two-wheeler riders died every hour, on average, across India. By 2023, this number rose to nine deaths per hour. About 1.5 million Indians died in road accidents in that decade. Two-wheelers accounted for the highest share (38%).

And it is getting worse. During this period, pedestrian deaths nearly tripled, those of two-wheeler riders nearly doubled, and cyclist deaths rose 13%. In contrast, every other category of road users–cars and jeeps, trucks, buses and autorickshaws–saw fewer deaths in 2023 when compared to 2014.

Data attribute these deaths overwhelmingly to overspeeding and lack of helmet use. But as we found earlier, police officials reporting these fatalities tend to blame the driver for most accidents, ignoring issues with road design, condition, signages etc.

For instance, expanding cities and extensive networks of highways have turned peri-urban and rural areas into points of conflict for residents navigating the roads and fast-moving vehicles passing by. The lack of access to good trauma care during what experts call the ‘golden hour’ when a victim could be saved compounds the tragedy.

On the other hand, cities are plagued by rising congestion, lack of enforcement of speed limits and sensitive zones, inadequate public transport options, and recently, the mad rush of the 10-minute delivery industry. Prachi Salve reports.

The Never-Ending Trauma

Cyclones batter islands in the Sundarbans repeatedly, and residents lose everything from homes, a sense of security and livelihoods. How do they deal with the trauma and anxiety resulting from repeated disasters?

Subhajit Naskar visited Sagar Islands to understand, and what he found is vital reading (accompanied by striking photographs):

“Every night while the rest of my family sleeps, I lie awake--the ticking of the clock echoing in my chest as the tide rises,” Shankar Bera from Mahishamari, Sagar Islands says.

“The smell of water that hits your home stays for days. It haunts you and dulls your senses,” Basumati Maiti says.

“It’s living in a bird’s nest. We constantly are in fear that a strong gust of wind could sweep everything away,” says fisherman Bikas Das.

The Bay of Bengal is among the most cyclone-prone regions on earth, and the 30-km long stretch of four islands of the Sundarbans (Sagar, Moushuni, Bakkhali-Fraserganj and G-Plot) is extremely vulnerable and frequently damaged by cyclonic surges.

Communities live on the edge, with homes damaged repeatedly, farming and fishing no longer remunerative, and access to services difficult. Many choose to migrate in search of work, but those who remain face food insecurity and mental health issues. The latter is often overlooked in official responses to disaster, Subhajit Naskar & Siddhanta Goswami report.