What Happens When Design Ignores Disability?

This week, how schools are failing children with special needs, and the devastation of Assam's pig farmers

Dear Reader

This week, I found myself thinking about A, who I went to college with. For a good part of four years, friends carried A—who needed crutches to walk—from the bus to his classroom on the second floor. It was a systemic failure that was clear as day to about 2,500 students, but something that the never-ending, swanky renovations did not notice or take into account.

What happens when architecture and planning ignores people with disabilities, or ‘special needs’? Our story of the week takes you through the data for Indian schools.

Elsewhere, African Swine Fever is devastating farms and destroying livelihoods in Assam, a state that has about 23% of pigs.

Access denied

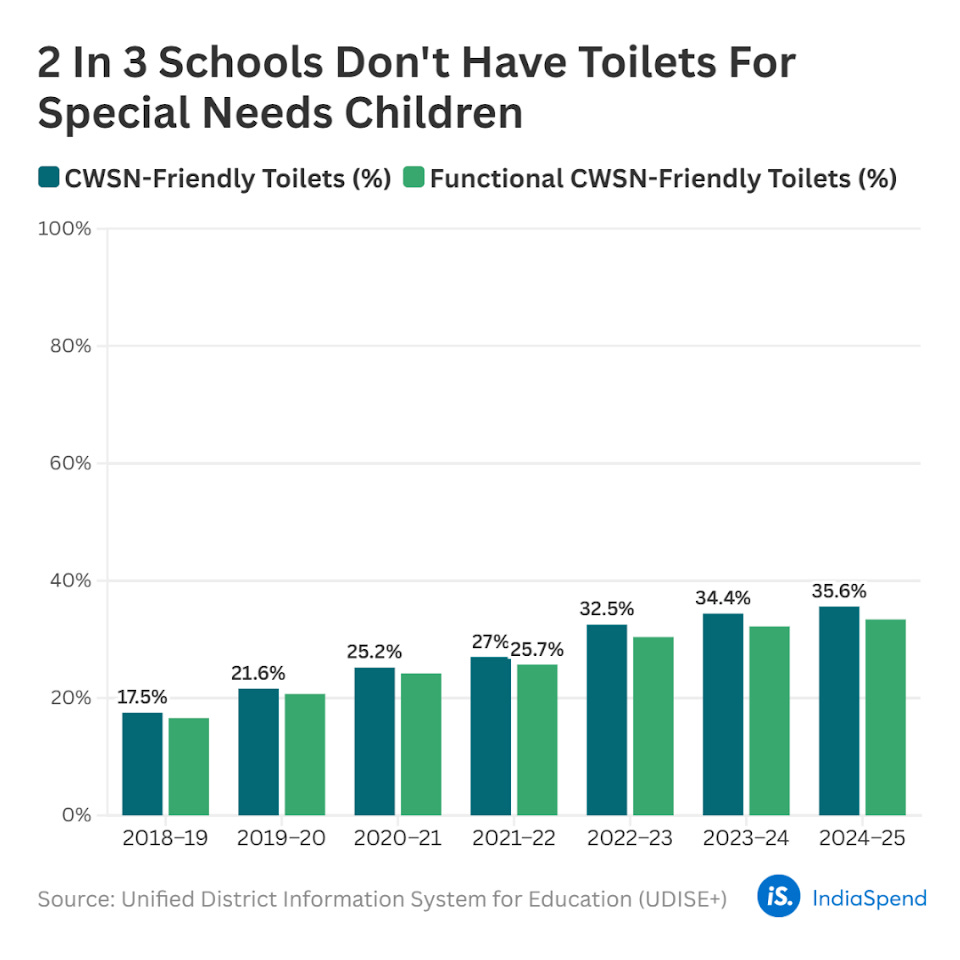

Two-thirds of India’s 1.5 million schools do not have toilets that are accessible to children with special needs (CWSN). Four in five schools said they have ramps, but nearly half do not have handrails, rendering them practically unusable.

In practice, says Deepali Kapoor of the inclusive education team at Pratham, teachers, helpers, or peers often step in to assist children. “This informal accommodation can inadvertently mask the underlying design problems.” (This is exactly what happened in the case of A.)

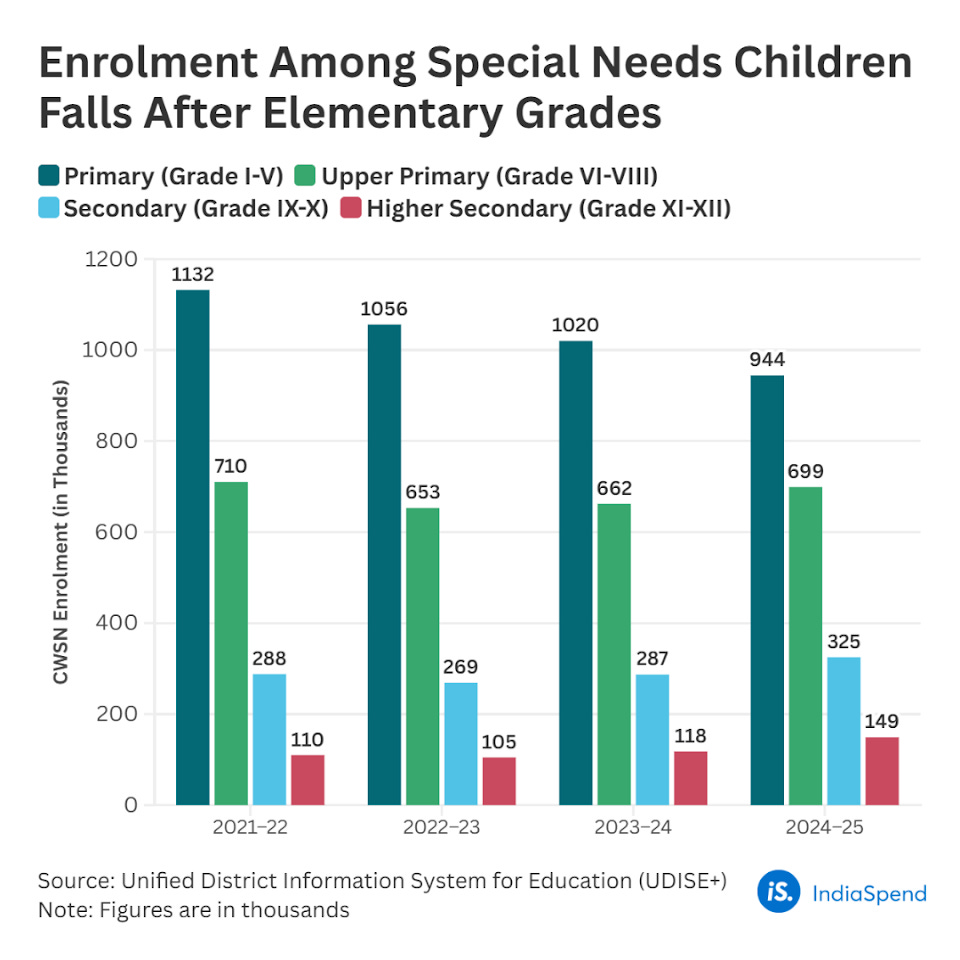

The absence of accessible infrastructure is leading to a decline in enrolment of students with special needs: Overall, children with special needs form 1% of enrolled students in elementary school (grades I-VIII), 0.9% in secondary (IX-X) and 0.5% in higher secondary (XI-XII) grades—indicating that fewer children with special needs make it to higher grades.

In addition, says Neeraj Trivedi, who heads organisational effectiveness at Pratham, children may be enrolled on paper but attend irregularly, leave early, or eventually drop out. What appears as “low enrollment” in administrative data may often be a series of rational withdrawals by families responding to an environment their child does not benefit from and succeed in. Vijay Jadhav takes stock, in this visuals-led analysis.

What’s ailing Assam’s pig farmers

In 2010, Binita and Mridul Buragohain started pig farming with two pigs. It took them 15 years to get to a herd of 75. In October last year, six pigs died and the others had to be culled—to prevent the spread of African Swine Fever (ASF). At the peak, the Buragohains earned a monthly profit of up to Rs 30,000-40,000 from piggery. Now, that income has vanished, and they are yet to receive the compensation of about Rs 6 lakh for this culling.

Pig farming grows faster and yields quicker returns than goat rearing, making it central to rural economies in many parts of Assam and Northeast India. Assam itself has about 23% of India’s pigs, livestock data show. Experts call for stringent biosecurity measures and handling to prevent spread. Sanskrita Bharadwaj reports how ASF—now endemic in India—is devastating the Northeast’s pig farming economy.

Before I sign off for this edition, I have a question for you. Did you make a resolution to exercise or play a sport this year? If so, how is it going so far?

And if you’re using public gyms, parks, or sports facilities—take a moment to notice who’s there and who isn’t. More on this next week.